New Edited Collection - The Patient's Wish to Die

/The Patient’s Wish to Die - Research, Ethics, and Palliative Care (2015), Edited by Christoph Rehmann-Sutter, Heike Gudat and Kathrin Ohnsorge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

This new edited collection is on Google books, but I haven't received a real copy yet. It is due to arrive in July and includes contributions from palliative care professionals and end of life care researchers. The book is divided into three broad sections on research, ethics and practice. I have a chapter in the book on 'Illness narratives, meaning making, and epistemic injustice in research at the end of life'.

Here is a short excerpt from the Introduction. Both the Introduction and my chapter are available in full on Google books. You can find more details about the book on the OUP website.

Introduction

In many countries there has been a public debate over several decades about the appropriate regulation of hastening death and other aspects of end-of-life care. The debates, however, often run in ideologically constrained circles and are not sensitive to the finer tuning of both the clinical reality and the subjective experiences and moral understandings of patients themselves as their lives draw to a close. This book brings together different research approaches to examine these phenomena, and makes them accessible to a broader audience than just the small, but international, ‘wish to die’ research community. Empirical research has been carried out for more than a decade on the phenomena of wishes to die and desires for a hastened death at the end of life. This book reflects the best currently available knowledge and research methodologies about patients’ wishes at the end of life, together with a series of ethical views and a discussion of the clinical implications for palliative care.

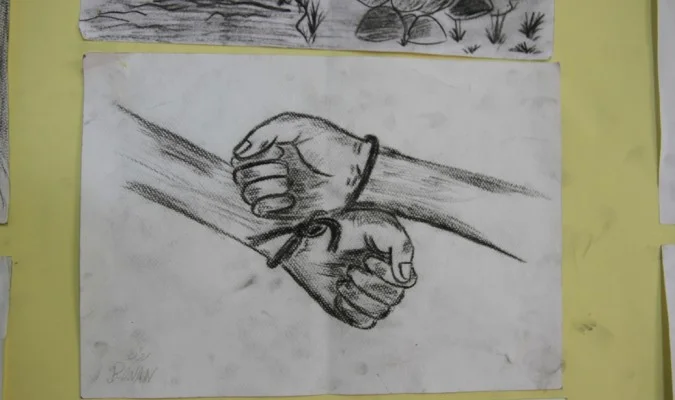

When somebody says, ‘I really want to die’, ‘I would prefer to be dead soon’, ‘Please,

let me die more quickly’—or similar things—the underlying wish expressed may be

very complex. In order to respond competently and compassionately, the healthcare

professional needs to grasp the dimensions immanent in wishes to die, both in general

and in regard to the concrete individually expressed concerns of the particular patient.

This requires deeper knowledge of the structure, the meanings, and the dynamics of

this phenomenon and of the interactions in which it is embedded. However, talking

with patients in depth about wish to die statements is still seen as challenging, and is

therefore often avoided by healthcare professionals (see Kohlwes et al. 2001). A superficial

understanding of the statement risks taking it at face value (just fulfilling what is

requested in the name of a superficially understood ‘patient autonomy’) without recognizing the patient fully as the person she or he is, who may be experiencing deeply

ambivalent feelings at the end of life and who might express this as one element within

a larger dialogue with healthcare professionals and relatives—and also in an inner dialogue

with her- or himself. Another risk would be to ‘medicalize’ the expressed wish

to die, i.e. to treat it as a sign or symptom of depression or anxiety in every single case

which automatically demands treatment. Both reactions can lead to suboptimal palliative

care, to shortcomings in the caring relationship, and, if things develop unhappily,

even to an unnecessary abandonment of the patient.

The intended audience of this book is primarily healthcare practitioners involved

in end-of-life care but also interdisciplinary scholars interested in palliative care and

medical ethics, including its specific challenges in the last phases of life. The book attempts to contribute in an open manner to the medical, ethical, and public debates on

this topic. It aims to be sensitive to the spiritual and existential dimensions of dying and

to the different cultural views that provide meaning to the individual.

We have invited some of the best-known palliative care research specialists and ethics

scholars from different countries to reflect on this sensitive issue based on an empirically

informed and patient-centred view. Many, but not all, of the authors discuss the

topic from a hermeneutical, phenomenological, or narrative perspective. The collection

includes palliative care practitioners and end-of-life scholars from countries where

different forms of assisted dying practices (such as assisted suicide or euthanasia) are

legalized and from other countries where they are not.